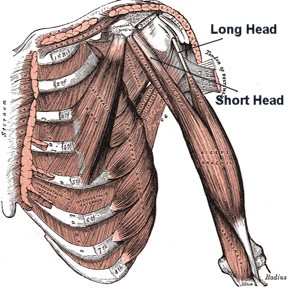

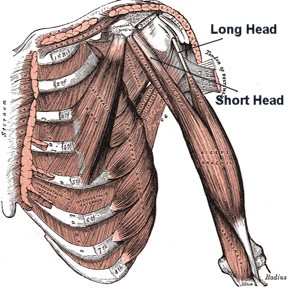

The biceps brachii muscle is a two-headed muscle responsible for

flexing the elbow and supinating the forearm (1). The long head

originates on the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula and

courses through the bicipital groove under the transverse

humeral ligament (1). The short head originates on the coracoid

process of the scapula (1). Both heads join near the insertion

of the deltoid to form a common muscle belly (1,2). Distally,

the muscle belly splits into two tendons with the stronger

tendon attaching to the radial tuberosity and the other tendon

attaching to the fascia of the forearm via the bicipital

aponeurosis (1,2).

Biceps tendinitis vs. biceps tendinosis

The phrase tendinitis implies inflammation, while the phrase

tendinosis implies collagen degeneration (3). Chronic tendinitis

may require 4-6 weeks to completely heal, while chronic

tendinosis may require 3-6 months for full recovery (3).

According to an article by Khan et al., an increasing body of

evidence supports that many overuse tendon injuries do not

involve inflammation (3). Therefore, these tendon injuries

should be labeled overuse tendinosis instead of overuse

tendinitis.

Supporting the rarity of tendinitis discussed in the

aforementioned Khan et al. article, Churgay estimates that

approximately 5% of patients with proximal bicep tendon injuries

suffer from primary biceps tendinitis, or inflammation of the

biceps tendon within the bicipital groove (4). Overhead and

repetitive shoulder rotation activities worsen the tendinitis,

causing the tendon to degenerate, thicken, and become irregular

(4). This collagen disorientation and disorganization is a

histologic trademark of tendinosis (3). Churgay notes that

athletes over age 35 or nonathletes are more likely to have

biceps tendinosis as a result of overuse over time (4). Primary

impingement, which occurs via mechanical compression of the

rotator cuff, biceps long head, and subacromial bursa between

the humeral head and the acromion, is considered the most common

cause of biceps tendinosis (5,4).

Subjective Exam

Patients may complain of sharp pain in the front of the shoulder

when reaching overhead, pain that radiates toward the neck or

down the front of the arm, dull achy pain at the front of the

shoulder after activity, and difficulty with daily activities

such as putting dishes away in overhead cabinets (6). Patients

with secondary impingement, which is a relative decrease in the

subacromial space with excessive anterior and superior migration

of the humeral head caused by instability in the glenohumeral

joint, may complain of numbness and tingling into the arm, pain

in the anterior/lateral shoulder, and pain in surrounding

musculature (5).

Objective Exam

The most common finding of proximal biceps tendon injury is

bicipital groove point tenderness (4). Many special tests,

including Yergason, Neer, Hawkins, and Speed, are useful in

implicating pathology of the biceps tendon (4). However, since

these tests also create impingement under the coracoacromial

arch, it is important to note that a rotator cuff lesion may

also elicit pain and contribute to a positive test result (4).

Conservative Treatment

Conservative treatment consists of rest from overhead activity

and ice (20 minutes at a time several times a day) (7). A doctor

may also recommend NSAIDs to reduce pain and swelling,

corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy (7).

Physical therapy management of proximal biceps tendon injuries

typically consists of three phases: phase one (restoration of

full PROM, pain management, and restoration of normal accessory

motion), phase two (AROM exercises and early strengthening), and

phase three (rotator cuff and periscapular strength training,

with a focus on enhancing dynamic stability) (2). For athletes,

a return to sport phase is initiated upon completion of the

rotator cuff and periscapular strength training phase (2).

Advancement through the phases depends on the chronicity and

irritability of the injury. A physical therapist will be best

able to guide patients through the proper exercise progression

based on pain, swelling, and motion. The American Academy of

Orthopaedic Surgeons has created a detailed handout that

clinicians and patients alike may find helpful titled "Shoulder

and Rotator Cuff Exercise Conditioning Program" (8). This

handout is available online at:

http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/PDFs/Rehab_Shoulder_5.pdf

Surgical Management

If a patient fails three months of conservative treatment,

surgery may be considered (4). During surgery, structures

causing impingement may be removed and the tendon may be

debrided (4). For serious tears or complete ruptures of the

biceps long head tendon, a biceps tenodesis may be performed

(4). This operation involves attaching the cut biceps tendon to

the bicipital groove or transverse humeral ligament with sutures

or anchors (4). A biceps tenotomy may also be performed (4).

This operation involves removal of the ruptured biceps tendon

from the glenohumeral joint and is "the procedure of choice" for

inactive patients over the age of 60 with a completely ruptured

biceps tendon (4).